Portosystemic Shunts In Your Dog And Cat

A Problem With Far Too Many Names:

Aka: PSS, Liver Shunts, Hepatic Shunts, Congenital Portosystemic Shunt (CPSS)

portosystemic vascular anomalies (PSVA) and portacaval shunt And also a similar disease: microvascular dysplasia (MVD) of the liver

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Go Here For MVD, A Similar Problem

Go Here For MVD, A Similar Problem

Hepatic Encephalopathy, A Possible Outcome Of Liver Shunts

Hepatic Encephalopathy, A Possible Outcome Of Liver Shunts

Hepatic Encephalopathy, Pet Owner Experience

Hepatic Encephalopathy, Pet Owner Experience

Click or tap on me for a fanciful Image of a simple extrahepatic (outside the liver) shunt

If you have come to this page, it is probably because your veterinarian told you that he/she suspects this could be your dog or cat’s problem. This is quite a complicated article because it deals with a complicated problem. I’ll do my best to keep it as simple as I can. If you want a more detailed, scientific explanation with lots of obscure medical terms, follow the article links that I have added. If it’s still unclear, let me know and I’ll try to walk you through it.

Some health problems your veterinarian deals with are easy to diagnose and easy to fix. Others are easy to diagnose and hard to fix. Hepatic shunts are both hard to diagnose and hard to fix. Diagnosis becomes more obvious when organs start to fail or when your dog or cat’s mental status begins to deteriorate. At that point, your pet is often suffering from some degree of hepatic encephalopathy.

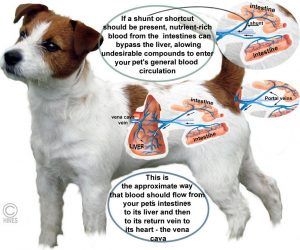

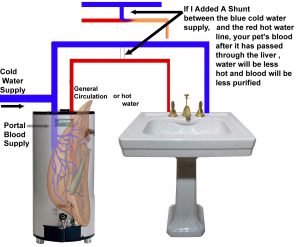

You could roughly compare the situation to your house’s plumbing system. If a small pipe with a slightly higher pressure jumped from the cold to the hot water side of the system bypassing the hot water heater (think liver) water would still come out of both faucets. In the case of plumbing, the hot water would be cooler than it should be. In the case of blood, a portion of the blood in the vein (the portal vein) that carries absorbed nutrients from your pet’s intestines would miss a vital step in detoxification that occurs in its liver and its liver would also be partially starved of nutrients.

That abnormal “pipe” that bypassed your pet’s liver (goes around the liver rather than through it) is called a shunt. Others call it an “anomalous” (i.e. abnormal, shouldn’t be there) blood vessel. Some call them “aberrant connections” – the same thing. Those veterinarians and physicians less inclined to be wordy just call them “liver shunts”.

Most developed while your pet was still in its mother’s womb (congenital portosystemic shunt, CPSS). But persistent higher-than-normal portal vein pressure due to blood flow obstructions or inflammation in the liver can cause them to form later in life (acquired portosystemic shunts). Shunts can sprout from blood vessels in many locations – both within the liver itself or at many points in the tangle of veins within your pet’s abdomen. There can be a single one, but on occasion several. In the smaller dog breeds, the shunt most commonly runs from one of the portal vein branches to the vena cava. In larger breed (e.g. Irish Wolfhounds), the shunt is often within the liver itself – the persistence of a duct that should have closed at birth. (read here) You can read more detailed scientific article abstracts on portosystemic shunts here, here & here. If you ask me and I will send you the full articles.

When you feed your pet, healthy nutrients are not the only things your pet absorbs. Bacterial fermentation and other processes in your pet’s intestines produce many products that are undesirable or toxic if they were to enter your pet’s general blood stream (its general circulation) unprocessed by its liver. (read here) One of the many jobs of your pet’s liver is to detoxify those products. So, nature designed a special many-branched vein (the portal vein) that drains nutrient-rich blood from your pet’s stomach wall and intestine as well as its pancreas and spleen (its splanchnic visceral organs) and sends it to the liver – not to the major vein in your pet’s abdomen (its vena cava). Once processed and detoxified in the liver, the portal vein eventually routs that blood on to the vena cava and from there on to the rest of the body.

Your pet’s liver needs a plentiful blood flow to develop normally. The rest of your pet’s body relies on ordinary arteries to supply that blood and nutrition. But in the special case of your dog or cat’s liver, although some of that blood does arrive through ordinary arteries, much of it (~80%) arrived through the portal vein from the digestive tract. When portal blood does not get there in sufficient amounts, the pet’s liver remains small (hypoplastic) and shriveled. If shunts develop after birth, the liver shrinks accordingly (atrophies). In some cases, surgery can reverse that process. (read here & here)

Hepatic Shunts That Dogs And Cats Were Born With = Congenital Shunts (CPSS)

Congenital shunts are the most common type veterinarians see. Most often, they short circuit the portal vein system somewhere outside of the liver but, as I mentioned, occasionally they are located with the liver itself. Most commonly, there is only one. But occasionally more than one exists in the same dog or cat. Owners of pets with CPSS usually notice that their dog or cat is not growing or behaving normally before your pet reaches a year of age. But a few dogs (and cats) are presented much later in life – often brought in because they have begun to show personality changes. Those changes could be confused with dog or cat “Alzheimer’s” disease (aka canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome or CCDS)

Veterinarians see these shunts most commonly in the toy dog breeds and purebred cats (Shih tzus, West Highlands, Maltese, Yorkies, Persian and Himalayan cats). There is even evidence that specific breeds of dogs have tendencies to breed-specific types of shunts. (read here) When the shunt is located within the liver itself (an intrahepatic shunt) it is most likely to be in a large purebred dog.

When a puppy or kitten is still in the womb, it relies on its mother’s liver to cleanse its blood just as it relies on its mother’s lungs to provide its oxygen. During that fetal period, its blood circulates by a different rout. Natural, normal, shunts short circuit the baby’s lungs (the ductus arteriosus and ductus venosus) and its foramen ovale, a natural opening in the heart wall, shunts blood from the right side of its heart to the left side. There are those that believe that liver shunts at that early age are also normal and that it is only their failure to close at birth as the others do that causes the problem.

Hepatic Shunts That Dogs And Cats Were Not Born With But That Developed Later = Acquired Hepatic Shunts

When normal blood flow through your dog or cat’s portal vein is restricted by liver disease or widespread inflammation, excessive blood pressure can builds up in your pet’s portal vein (= portal hypertension). That increased blood pressure is thought to be the reasons that shunts (new blood channels) sometimes form that bypass the dog or cat’s liver. Those blood channels were not present at birth. These are generally multiple small shunts located within the liver tissue itself. Cholangiohepatitis, also called triad disease, is thought to be an underlying cause of many such chronic inflammations in cats. There have been a few feline cases in which the shunt problem was apparently brought on by a birth defect (liver fibrosis) ; but the abnormal blood channels formed later due to increased portal vein pressure. (read here)

Unfortunately, neither veterinarians nor physicians have found a way to surgically fix these acquired shunt problems. The best we can offer your pet is to attempt to locate and lessen the underlying causes of liver inflammation and to place your pet on medications (e.g. lactulose and antibiotics, etc.) that might decrease the toxins entering its circulation. Special diets can be helpful here too. Many more publications deal with these types of shunts in dogs than cats. But you can view one specifically on cats here. And ask me for Tillson2002.

What Are Some Of The Locations Where Hepatic Shunts Have Been Found?

Shunts Outside Of Your Pet’s Liver – Extrahepatic locations

These are all locations within your pet’s abdomen. They start at various locations but all end up emptying into the pet’s main abdominal vein, the posterior vena cava (or occasionally into your pet’s azygos or phrenic veins which are alternative routs for blood to get back to the heart). When they begin at the spleen and end at the vena cava, they are called spleno-caval shunts. When they begin at the spleen and end at the azygos vein, they are called spleno-azygos, going to the phrenic vein, spleno-phrenic. When they begin at the stomach, gastro-caval or gastro-azygos etc. In cats, shunts beginning at the stomach are the most common.

The azygos vein and phrenic veins are of smaller diameter than your pet’s vena cava. That is though to allow for less blood to bypass your pet’s liver. So, symptoms of those types of shunts are often less severe than those of shunts that end in the much bigger vena cava. A study found that dogs that have had unsuccessful surgery to close an extrahepatic shunt(s) are at greater risk of developing ammonium urate kidney and bladder stones than those that were completely alleviated. (read here)

Shunts Inside Of Your Pet’s Liver – Intrahepatic locations

All dog and cat fetuses have that large shunt I mentioned earlier, their ductus venosus, that carries blood quickly around the baby’s liver to the heart. Since its mother’s liver does the work of filtering out toxins, storing sugar, and producing protein for her unborn babies, the fetal baby’s own liver function is not required. This ductus venosus shunt is supposed to close down shortly before or shortly after birth as the baby’s liver begins to work on its own. In some youngsters, the shunt doesn’t close down; then it is then called a “Patent (open) Ductus Venosus”, or an intrahepatic shunt. These intrahepatic shunts are much less common than extrahepatic shunts. They generally occur in larger breeds such as Irish wolfhounds, and Old English Sheepdogs (in which patent ductus venosus is thought to be a common genetic defect) Australian cattle dogs and golden retrievers. An occasional cat will be born with this type of shunt as well.

Microvascular Dysplasia (MVD)

A different problem than portosystemic shunts, but one that can cause similar effects. Read in more detailed about this problem here

When blood circulates abnormal through your pet’s liver through the tiny blood channels (sinusoids or microvascular channels) that are abundant in it, liver cells (hepatocytes) again lose their ability to cleanse and detoxify that nutrient-rich intestinal blood. This inherited problem is most common in the toy breeds of dogs (e.g. Maltese, Yorkies, Cairn terriers, etc.). Veterinarians believe that in these small dogs, this problem is considerably more common than the larger shunts (portosystemic ones) that I discussed up until now. Luckily, this malformation usually causes much less damage than the large shunts. Most of these dogs lead a relatively normal life – the only sign being an increase in their blood bile acid level. Problems can arise, however when dogs with this condition are given drugs that rely on the liver to be cleared from their body. Pets that go unexpectedly “deep” under sedation or anesthesia might clue your veterinarian that MVD needs to be ruled out as a contributing cause. Many also suspect that breeding for “tea cup” size cuties increases the risk of breeding for this disease as well.

When this genetic problem causes owner concern, it is generally due to the pet being smaller than its littermates or a finicky eater. I believe that dog breeders whose puppies and breeding stock are at confirmed risk of MVD ought to inform potential purchasers of that fact. If it has occurred in your breeding stock, it might be wise to do a bile acid screen on all the puppies you produce. The same goes for luxating (“popping”) knee caps. If you are the purchaser, request both.

Veterinarians often suspect an MVD problem when they find that your pet’s serum bile acid level is abnormally high but other blood test values that would suggest a portohepatic shunt are normal (i.e. normal red blood cell size, normal BUN and creatinine, normal protein C, normal cholesterol, normal ammonia). On rare occasion, dogs will have both MVD and a portohepatic shunt. Measuring your pet’s blood ammonia level is an unreliable way to diagnose either disease. Measuring its bile acid level is a considerably better way. When MVD pets have no related health issues, there is no need for them to receive special diets or other medications. If you are still worried, have Cornell’s veterinary lab run the protein C test (not the same as c-reactive protein). If it’s normal, stop worrying.

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is a liver problem that affects your pet’s brain. The condition is often the end result of liver shunts, but any disease that decreases the ability of your pet’s liver to do its work can cause hepatic encephalopathy as well. I devoted an entire article to that problem. You can read it here.

What Signs Or Symptoms Might I See If My Dog or Cat Has One Or More Hepatic Shunts?

The symptoms owners report in their pets with PSS are quite vague, and they are extremely variable. These symptoms tend to come and go, occasionally being worse after a meal. The most common sign is a dog or a cat that either started out smaller than the rest of its litter or failed to grow at a normal rate after birth.

Many of these pets are picky eaters. Some have intermittent bouts of diarrhea (but in a few, constipation is an issue). Others have vomiting issues. Many were initially diagnosed as having inflammatory bowl issues (which they could have as well). Some drink and urinate more than normally and many have more infections and other reasons to visit their veterinarian than they ought to. They many have been put on antibiotics many times in the past and often improved on those antibiotics – even though the underlying shunt problem was missed. That is because those antibiotics decrease the number of bacteria that were creating toxic products in your pet’s intestines that their weakened liver could not detoxify. Your pet’s liver is also responsible for storing glycogen, a compound necessary to maintain constant blood sugar level. That is why dogs with PSS are more likely to have been diagnosed with hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) than other dogs.

So, you can see how the problem can be easily missed or mistakenly attributed to something else. But bells start to ring in your veterinarian’s head when the dog or cat’s mental attitude changes. It might develop seizures or becomes aggressive for no obvious reason. Some just appear spacey or dazed. Others seem just too quiet. Other dogs and cats become disorientation or demented (walking in circles, getting stuck in corners, forgetting their training). The bells ring loud when the owners have noticed that those problems are worse shortly after their pet eats. Those are all signs of hepatic encephalopathy that you can read more about through the link I suggested to you earlier.

Bells also ring when urinary tract stones are found to contain ammonium biurate, a product of the excess ammonia in their system. It was often the UTI signs you reported or an abnormal urinalysis that got your vet looking for stones in the first place. Bells ring as well when a pet is slow to come out of anesthesia or tranquilization. That is because its liver isn’t up to detoxifying those compounds as well as it should. Common signs in cats include excessive drooling that is not due to tooth and gum disease and having being runts of the litter. Many are also found to be anemic.

What Blood And Lab Test Results For My Pet Might Be Abnormal?

The key diagnostic test for this group of diseases is a measurement of your dog or cat’s blood bile acid level. Not all pets with high bile acid levels have portosystemic shunts or MVD. But almost all pets with portosystemic shunts or MVD have higher than normal blood bile acid levels. When the bile acid results for your pet are not dramatically high, a sample taken before a meal and one taken a few hours after the meal may help in decision-making. The level often rises after a meal in pets with PSS. But please remember that a variety of liver problems – not just PSS – can cause elevated bile acid readings.

Theoretically, dogs and cats with portosystemic shunts should have higher-than-normal blood ammonia levels too. But an accurate ammonia assay is quite a difficult test to run. Some centers still attempt it; but the methods and interpretation of the results differ from institution to institution. Here in Texas, A&M performs a single fasting ammonia level assay as part of their PSS work up. In Australia, some challenge the pet suspected of having PSS with an oral or rectal dose of ammonium chloride to see if their liver can detoxify it (that test is not without risk). At the vet school in Utrecht, blood ammonia assays are still an important part of PSS diagnosis, and they are repeated during follow up to judge the success of surgery when it is attempted. But many other veterinarians question if blood ammonia levels correlate directly to the symptoms a pet is experiencing. (read here)

Other blood test results that are often found to be abnormal are not specific for portosystemic shunts. That is, a lot of other health problems could also be the cause. But here they are :

1) Many of these pets are anemic and the red blood cells they do have are often, but not always, smaller than normal (microcytic anemia). That occurs because these pets have an iron deficiency.

2) Many of these pets have lower than normal blood BUN and creatinine levels. Many also have lower than normal blood albumin, glucose and cholesterol levels because producing those compounds was one of the liver’s responsibilities.

3) Finding that a urinary tract stone (calculus) that is composed of ammonium biurate makes a PSS diagnosis quite likely. These are most often found in older pets that have dealt with a PSS issue for a long time. (read here & here) Those pets may not have even been suspected of having PSS; but finding these distinctive, spiked crystals should be enough to consider it now.

4) Some of these affected dogs and cats have elevated liver enzyme tests (ALT & AlkPhos) or slowed blood clotting tests – all of which point to a liver problem. But just as many pets with confirmed PSS do not show those changes.

5) When the diagnosis is still in doubt, you can have the veterinary laboratory at Cornell University run a protein-C test to assist with the diagnosis. But, ultimately, you will need to rely on the radiology (imaging) department of a major veterinary institution to make the diagnosis certain. Read about that below:

You see, your veterinary surgeon needs to know more than just the fact that your dog or cat has shunts. The surgeon needs to know exactly where the/those shunt(s) are located before deciding if surgery is an option. Only imaging techniques can do that.

Imaging Techniques: Only One Imaging Method Might Be Required

X-rays

Ordinary x-rays (radiographs) won’t do. They do not reveal hepatic shunts. But x-rays might reveal that your pet’s liver is smaller than it should be. That, plus symptoms, might even prompt a liver biopsy. But biopsies do not confirm or rule out PSS either. If your dog or cat has developed kidney or bladder stones due to PSS, those might show up on a radiograph too. But one mineral class of stone looks too much like another on x-rays, and many biurate stones are too porous (radiolucent) to even show up on x-rays. Although they might show up on ultrasound imaging if they are large enough.

Ultrasound Doppler Ultrasound, Echocardiography

The ultrasound apparatus of choice when circulatory issues are involved is called a Doppler ultrasound. This type of ultrasound machine is particularly good at visualizing blood flowing through channels and vessels and judging its speed and pressure. It is a sophisticated procedure that requires an ultrasonographer (the unit’s operator) with considerable talent and experience. Locating the shunt can sometimes be aided by injecting an agitated (frothy) sample of the pet’s own blood and following the air bubbles (microbubbles) produced as they move through the pet’s circulatory system.

CAT Scans – CT Angiography, Computer Tomography

Some veterinary institutions with large financial resources find CAT scans, enhanced with an intravenous injection of contrast enhancing material (“dyes”) that highlight the blood vessel image, a preferable way to locate portosystemic shunts. Like all forms of imaging, the operator’s perceptiveness (learned painstakingly over time) influence success more than the particular procedure used.

Scintigraphy Nuclear Scintigraphy

This technique follows the movement of a radioactive material (radioisotopes), placed in your dog or cat’s colon, through the colon wall, into your pet’s blood stream, then through its liver and on into its general circulation. That is the rout that 85% of the material takes in normal dogs and cats. When less of it goes through the liver but still ends up in the general circulation (visualized in the heart), we know that there must be an alternate rout (a shunt) through which it got there. However, we do not know where the shunt is, and we do not know how many there are. Because your pet is radioactive for a short period after the test, they must spend the night at the animal hospital. But the procedure is painless, and no sedation is required. The standard scintigraphy procedure yields a 2-dimensional (flat) image. If the apparatus gives a 3-D image, a PET scanner scanner was used. If the radioactive material was injected directly into the spleen, the image produced is called a nuclear portogram.

stopped spell check here

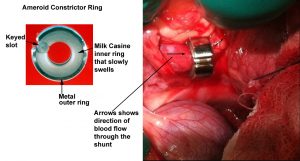

All the scintillation methods have the advantage of telling your veterinarian how much blood is actually going through your pet’s liver normally and how much isn’t. If not much blood is abnormally bypassing your pet’s liver, perhaps surgery is unnecessary. If a lot of blood is bypassing the liver, it might not be advisable to close the shunt completely in a single operation and a method that slowly squeezes the shunt closed might be best (cellophane banding or ameroid constrictor that I write about later).

Portography aka Portovenography

This technique uses a series of ordinary x-rays taken after an iodine-containing dye has been injected into your pet’s portal vein system. This dye shows up on x-rays and, by tracing its flow, you can see how blood is moving around in the body. The problem is, one generally has to open the pet surgically to inject this dye into the portal vein. However, some radiologists have had success injecting the dye into the pet’s spleen through the body wall using ultrasound to guide them (the University of Tennessee apparently gets the dye to the correct location through a long catheter placed in the dog or cat’s neck). Like scintigraphy and CAT scans, one can get a rough estimate of the size of the shunt and the advisability of closing it suddenly, by the amount of the dye that goes to the liver versus the amount that goes around it through the shunt(s). As I said before, big shunts are best closed slowly. Others make this decision during the surgery by monitoring pressure in the pet’s portal vein. You do not want that pressure to rise too high. High-pressure means that the pet’s liver is not capable of suddenly handling the large amount of blood it has suddenly been provided.

MRI – Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRIs can also be used to locate shunts in dogs and cats. It is not commonly the method of choice because of the time involved in performing the procedure and its expense.

Exploratory Surgery – laparotomy

This is the least effective way to confirm that your pet has a portosystemic shunt and to confirm its location. But many pet owners just don’t have the financial means to afford the better options. Others may live far from institutions that have the capability of performing anything else. It is quite easy to miss seeing a shunt during surgery. The only advantage, other than cost, is that the veterinarian can examine all your pets’ abdominal organs and, perhaps, find other things that need correcting.

Can My Veterinarian Fix My Pet’s Problem Surgically?

Yes. In many cases a specialized veterinary surgeon can.

But this is not something you would want a general practice veterinarian to attempt. You want this performed at a large veterinary center by a board certified veterinary surgeon who has done many of the same surgeries in the past. One backed up by a team of seasoned technicians and assisting veterinary internists.

To get around the problem of suddenly overloading your pet’s liver with a new blood supply, veterinarians can do four things: The first, a series of operations, each tightening the suture wrapped around the shunt a little bit more. They can attach a device that measures blood pressure in the portal vein and tighten the suture (often silk) just enough so that the pressure does not rise too high. Or, they can apply a band around the shunt that slowly tightens by itself over time. The first of those used was a band of cellophane tape. Cellophane implants are somewhat irritating to the body. As your pet’s immune system destroys it, scarring occurs around it. That scarring eventually squeezes the shunt shut – but slowly enough for your pet’s liver to adjust to the new, increased, blood supply. The second automatic constrictor is the ameroid ring (ameroid constrictor).

When the shunt has been determined to be inside of your pet’s liver, surgical treatment much more difficult. These are the shunts that are most common in large dog breeds. Some have been successfully closed with ameroid constrictor rings too – but it is a complicated and difficult surgery. More recently, veterinarians have been closing them successfully using intravenous wire coils that block blood from passing through the shunt. Usually, this apparatus is introduced through a small cut in your dog or cat’s neck (jugular vein approach) or thigh (femoral vein approach).

I do not know of any surgery that can correct shunts that your pet was not born with. That is, shunts that your pet developed later in life due to some disease of the liver or other health issue. Those are the acquired hepatic shunts. Some shunts are so large and have deprived the liver of proper blood flow for so long that it would be inadvisable to shut them off completely. But those pets usually improve significantly even if the shunt is only partially closed. Some surgeons suggest a first surgery to constrict the shunt partially and a second or even third to constrict it even more or completely shut it off.

What Might It Cost To Have This Surgery Performed On My Dog Or Cat?

These are costs of these procedures at some of the institutions I talk about in my article. In most cases, it was the surgeon who furnished me with the information. Those were the costs quoted to me when I wrote this article. They are no doubt higher today. Because portosystemic shunts are often birth defects, I believe that the majority of pet health insurance policies will not cover them. However, in a few instances, these shunts form after liver injury. Perhaps, some of the insurance companies offering pet insurance would consider covering the cost of portosystemic shunt surgery if evidence or history of a traumatic cause was present.

At the Veterinary School, University of California, Davis, the workup required to confirm or rule out a portohepatic shunt often ran about $1,000. When discovered, closure of a typical single shunt then costs $4,600 – $6,800 in addition. The precise cost to operate on your pet cannot be precisely determined beforehand because it is impossible to anticipate all the testing that might be required or unforeseen obstacles that might be encountered by your surgeon during surgery. When an operable shunt is discovered to be within your pet’s liver itself (an intrahepatic shunt), the veterinarians at Davis sometimes attempted to close it with tiny metal coils advanced into the shunt from the leg through an IV catheter placed in your pet’s leg (similar to how heart catheterization is performed in us humans). That cost of that procedure at Davis was quoted to me as $8,600-$12,000. All of these prices may now have risen due to inflation.

At Michigan State College of Veterinary medicine, the workup required to confirm or rule out a portohepatic shunt and visualize it prior to surgery often ran about $1,650. A Typical surgery costs to correct a shunt were $2,500 – more if urinary tract stones (calculi) need to be removed; a bit less if not. $3,500 was not an unusual bill for the total service. All of these prices may now have risen due to inflation.

At Auburn University, College of Veterinary Medicine, the initial workup ran from $800 – $1,500. The cost of the surgery was typically around $2,000. The owner’s final bill was usually $2,500 – $3,500. If complications or an extended hospital stay were required, the cost would be proportionately higher. All of these prices may now have risen due to inflation.

At my alma mater, Texas A&M University, the workup, surgery and post-operative care cost the pet owner about $4,000. All of these prices may now have risen due to inflation.

At Queen’s Veterinary Hospital, University of Cambridge, UK, diagnosis and pre-surgical workup usually cost $1,850- $2,316 (1,200-£1,500) The surgery itself typically costs $3,089-$6,179 (2,000-£4,000). Those estimates did not include the VAT (tax), which, I believe, was 20%. The Willows Centre in Solihull, UK also performed this surgery. Their surgeon would not venture an average cost because he found the price too variable.

At the Veterinary College, Utrecht, Netherlands, presurgical diagnostic work up for portosystemic shunts often cost $376 (€350). That is the cost when bile acids, ammonia levels and ultrasound exam are sufficient to be reasonably certain of the diagnosis beforehand. If a CAT scan proved necessary, the cost was an additional $752 (= €700). When they felt the surgery could be successfully performed, their cost to do it was about $2,148-$2,686 (2,000-€2,500).

If you would like to add costs at the date you read this article. Let me know and I will add them.

Are There Less Invasive Forms Of Surgery That I Might Consider? Minimally Invasive Techniques

Yes,

Several of the surgical procedure I previously mentioned can be accomplished either by threading coils or shunt-blocking agents (vascular plugs) through a large vein of the dog’s neck (its jugular vein) or its leg (its femoral vein). Bands that constrict and close shunts can also be placed within the body through small incisions and then guided into correct placement with a laparoscope.

Procedures that thread these apparatus up veins are usually done by interventional radiologists within the school’s radiology department. Because those veterinarians can measure blood flow in real time, they may also have the option to place metal frameworks (stents), similar to those used in the heart, to enlarge blood vessels that are too narrow to accept the additional blood flow when the shunt is closed. These advanced techniques are quite new to veterinary medicine. One might still consider them experimental. Pioneers in these procedures are The Animal Medical Center in New York City and the Veterinary School at Purdue University.

What Is The Overall Success Rate Of This Surgery?

The success rate for this complicated procedure is good. However, success is highly dependent on the individual skill of the surgeon, the backup support team and the imaging machines at their disposal. Many facilities claim an 85% success rate in dogs in correcting portosystemic shunts. The success rates claimed in cats are lower (~ 66% in one Tufts study in cats) (read here) and 55% in another RVC, London study. (read here)

I suppose I should tell you something that is generally only whispered. Surgeons tend to overstate their success rates in all fields of medicine. This is not a form of deception, it is just human nature to want to succeed, to be successful and to maintain an optimistic attitude. Does a coach ever tell his team that they are not likely to win? Studies in human medicine found overstatement of success as high as 35%. (read here & here) In veterinary medicine a similar bias toward claims of surgical success also occurs (read here & here)

So in many cases, your dog or cat’s success might be better defined as an improvement in your pet’s condition, not necessarily a complete elimination of the problem, not necessarily a cure. Not all shunts can be completely blocked off safely. (read here) Some suggest that in only about 68% of the cases is that possible. (read here)

Preparing Your Dog Or Cat For The Surgery

Many pets with portosystemic shunts arrive at an animal hospital only after the shunt(s) are producing pronounced symptoms. Those pets need to be stabilized with appropriate diets and medication before surgery is attempted. Low protein diets can help accomplish that. So can lactulose and antibiotics. Some facilities, such as Texas A&M, make the decision on when it is safe to operate based on your pet’s blood ammonia level. At the Bristol, UK facility, dogs typically receive a 4-wk course of oral lactulose, ampicillin, and Royal Canin Hepatic™ dog food. Pre-op treatment for PSS are quite similar around the world. (read here) Other commonly used antibiotic options are neomycin and metronidazole.

It is important that dog and cats planning to undergo shunt surgery be in the best possible physical condition. Pets with portosystemic shunts are higher risk anesthesia subjects, they are prone to hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) and they metabolize and distribute drugs differently in their bodies than pets with healthy livers. Pets prone to convulsions might need anti-epileptic medications (e.g. levetiracetam) prior to surgery as well.

What Kind Of Aftercare Will Be Required?

Many of these surgical patients are immature or thin animals that have a hard time maintaining their body temperature while recovering from anesthesia. The surgical nurses will tend to that. Blood sugar levels will be monitored and appropriate sugar solutions given if required. Dogs with abnormal liver function are prone to hypoglycemia. That is why it is important that these pets resume eating as soon after surgery as possible (many do not fast them until just before surgery for the same reason). A healthy liver is also important for normal blood clotting. So, the staff will be on the lookout for abnormal post-surgical bleeding as well.

The nurses will also be on the alert for seizures – they are not that uncommon in pets whose shunts have been closed. Vets do not know why. Another serious post-surgical complication is abnormally high a blood pressure in the portal vein (portal hypertension) subsequent to the shunt closing. Some signs associated with that are bloating (fluid leakage into the abdomen=ascites), low blood pressure in the rest of the body, pale gums, and intestinal bleeding (bloody diarrhea). These usually resolve quickly with supportive care. But in a few cases, the shunt must be loosened sufficiently to stop these side effects.

When the surgery was successful, it should not be too long before your surgeon can confirm (using ultrasound) that your pet’s liver is increasing in volume toward a healthy size. (read here)

Generally, the same lower-protein diets, lactulose and antibiotics given before the surgery are continued after the surgery for a number of weeks. There will be pets that have gone through this surgery that will do best when those hepatic diets, as well as lactulose, are fed indefinitely.

Periodic bile acid measurements are also a great way to gauge the speed of your pet’s recovery. A return to normal blood albumin level and improvement in any other presurgical blood test abnormalities are also excellent signs. Expect that to take 3–6 months.

Cats seem to have more post-surgical complications than dogs. Recovery is also a bit more challenging for older dogs than for those less than a year of age when the surgery is performed. A small portion of the pets will develop new shunts when their livers cannot bear the burden of the increased blood supply it now receives.

The presurgical imaging techniques I mentioned earlier are quite important for anticipating post-surgical complications. Dogs and cats with multiple shunts, large shunts, stunted portal veins, intrahepatic shunts, and extremely small liver-to-body mass ratios all need careful watching in the weeks following surgery. As I indicated before, complications are said to be more frequent in cats than dogs – although some surgeons dispute that. Perhaps it is greater familiarity with performing this procedure in cats that accounts for this. Inquire as to the relative dog and cat case loads at the facilities you visit.

Might Medications Or Diet Changes As An Alternative To Surgery Help My Pet?

Every published study suggests that the quality of life of dogs and cats that have shunt problems corrected surgically is likely to be better than the quality of life of pets that do not undergo the surgery. However, those studies may be skewed due to the tendency to study dogs and cats that are already showing severe signs. They are also probably somewhat biased because veterinary centers promoting shunt surgery are generating these articles. No two portosystemic shunts are exactly alike. When the shunt(s) are small or when your dog or cat’s body has successfully adapted to them, some pets live long lives with just medical and nutritional management.

A key goal in medical management is to decrease the amount of ammonia that enters your pet’s body through its intestine. That can be accomplished by not overloading your pet with dietary protein (the source of much of its blood ammonia). It can also be accomplished by providing oral antibiotics to reduce the amount of ammonia that bacteria in your pet’s gut produce. Giving your dog or cat products that bind to ammonia allow some of the ammonia it to be expelled in its stool (ie lactulose). Altering your pet’s feeding routine (giving smaller, more frequent feedings) should be helpful as well. Some say that egg, dairy and soy protein are less likely to generate high ammonia levels. I do not believe that has been scientifically confirmed. Others report that increased dietary fiber is helpful. I do not believe that that has been proven either, but there is no harm in trying. I certainly would. As you may know, I personally prefer it when pet owners like you make their dog and cat’s diets from wholesome ingredients at home. But I have no proof that that is preferable to veterinarian-purchased prescription diets either. No one really does. Remember, not enough protein in your pet’s diet to meet its body’s requirements is just as bad or worse than too much protein. Some, suggest a zinc supplement. Too much zinc is also toxic. Periodic blood bile acid assays, and blood albumin levels included in a general blood analysis are the best way to adjust and modify your dog or cat’s dietary program as time goes by. If surgery is not an option, you might find some other possible treatment options in my hepatic encephalopathy article.

Cholestyramine

I have no experience giving this medication to dogs or cat. I know of no veterinarian who has. But cholestyramine showed positive results in some preliminary liver-management experiments. (read here) It has also been found to lower ammonia levels in dogs. (read here) Go to my hepatic encephalopathy article and read more about this medication if you wish. I would appreciate any feed back on that or other bile acid sequestrants that you might provide.

If your dog or cat suffers from portosystemic shunts, any medication that requires your pet’s liver for detoxification and/or elimination is best avoided – or the dose reduced.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.